The Cognitive Crossroads of Writing and AI

On a quiet Thursday afternoon, Ms. Lopez lingered at her desk as the last streaks of daylight slipped through the blinds. A pile of essays leaned against her laptop, where a cursor blinked steadily on ChatGPT’s screen — a small pulse of possibility. Like many teachers, she was thinking about a question that no longer feels hypothetical: If AI can write, what happens to the thinking behind the words?

It’s the conversation echoing from staff rooms to district meetings. Everyone knows the reality — students are using AI to write. What remains uncertain is what that means for learning itself. Does AI stretch the mind, or does it quietly take over its work?

That uncertainty caught the attention of researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Their 2024 study, “Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt When Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Tasks” (MIT Media Lab), offers one of the first neurological examinations of what actually happens inside the brain when people write with AI. Through EEG scans, linguistic mapping, and behavioral analysis, the researchers found that AI can help organize and polish writing — yet it may also sap mental engagement, leaving behind what they term cognitive debt.

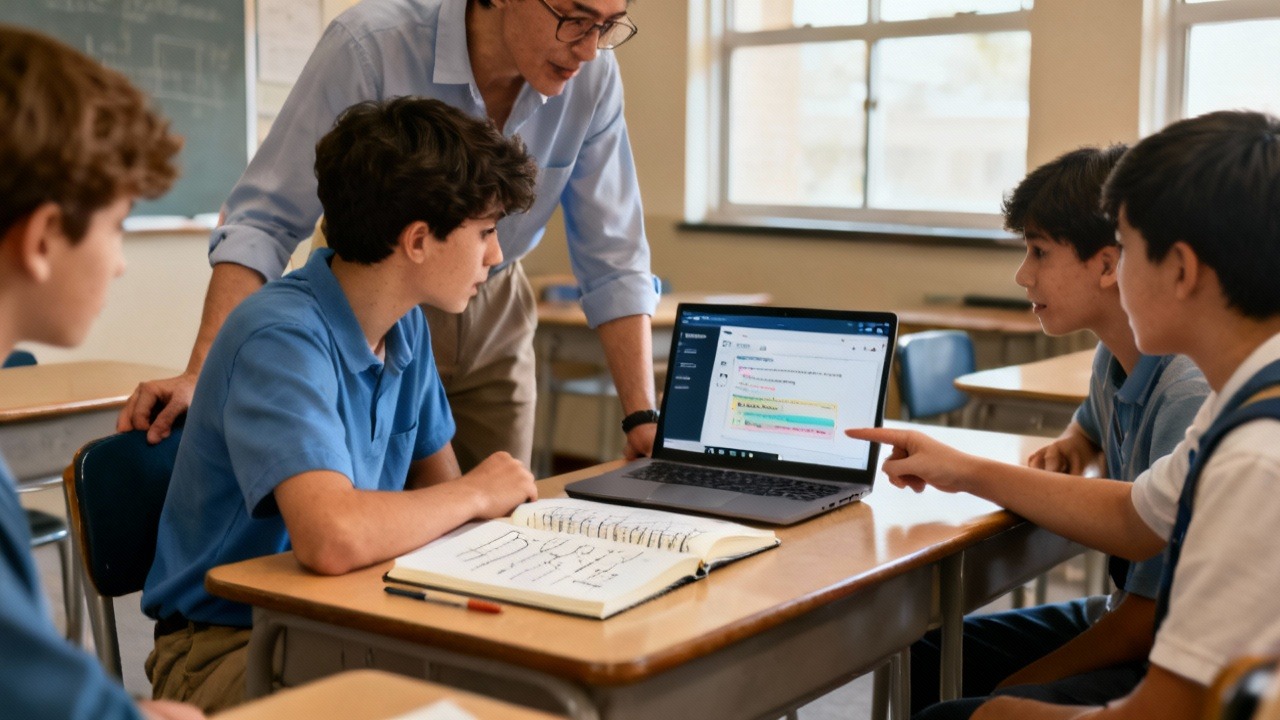

In classrooms where AI essay graders and essay checkers are now as familiar as grammar rubrics, that finding feels particularly relevant. The question for teachers is no longer whether to use AI, but how to use it without losing the reflective work that writing demands.

Inside the MIT Study: Neural Engagement and Cognitive Debt

Over several months, fifty-four participants wrote essays in three ways: entirely on their own (“Brain-only”), with a search engine, and with a large language model — ChatGPT. Each wore an EEG headset measuring neural connectivity, especially in the regions tied to concentration, working memory, and creative synthesis.

The data were hard to ignore. Participants who relied on AI showed reduced neural interconnectivity, particularly within the alpha and beta frequency bands associated with focus and integration. In plain language: the brain was less active when the AI helped. With repeated use, neural engagement declined further — a pattern researchers described as mental outsourcing.

Later, when those same participants wrote without AI, their prose weakened. Many forgot details from earlier drafts. Sentences flattened. Confidence wavered. Several described the result as “less mine.”

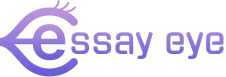

That phrase captures something more than neuroscience — it hints at ownership, identity, and pride. The essays produced with AI were smoother, grammatically stronger, and well-structured — yet, as human raters noted, they felt polished but hollow.

This tension between fluency and authenticity now defines the new frontier of writing instruction. Teachers must help students use AI to refine their ideas without letting it replace their thought.

From Laboratory to Classroom: The Same Paradox in Practice

Across the country, teachers are observing the same contradiction the MIT team documented. A high-school English teacher in Sacramento, for instance, noticed that his students’ essays became cleaner this year — fewer errors, sharper syntax. But he also noticed something missing: their voices.

That observation matches the study’s linguistic analysis. The AI-assisted essays shared similar phrasing, pacing, and transitional patterns — as if composed by a single unseen author. When students depend on large language models, they often unconsciously mimic the model’s rhythm and tone. The result is professional but impersonal prose.

For educators, that poses a profound question. Writing has never been merely transcription; it’s thinking in motion — a rehearsal for reasoning. When AI drafts a sentence, what happens to the cognitive struggle behind it? As psychologist Daniel Willingham famously put it, “Memory is the residue of thought.” If students think less, they remember less — and learn less.

The MIT findings don’t argue against using AI essay graders or tools for teachers. They invite a shift in perspective: AI should not be treated as a ghostwriter, but as a reflective surface — a mirror that helps students see and strengthen their own reasoning.

Rethinking Essay Design: Reflection as Safeguard

If there is one clear implication from the MIT research, it’s this: engagement matters more than efficiency. Students who remained mentally involved — outlining before prompting, questioning AI responses, rewriting in their own words — demonstrated higher recall and conceptual depth.

That insight points toward a practical balance. The solution isn’t prohibition; it’s design. Teachers can create writing experiences that make space for reflection and ownership, even while using AI to grade essays or provide feedback.

A few strategies gaining momentum include:

- Outline First, Generate Later.

Students compose a thesis or outline before using any AI tool. This preserves the “front-end” of cognition — where critical thinking and argument formation occur. - Critique the Machine.

After receiving AI suggestions, students annotate the feedback. Which ideas help? Which dilute meaning? This transforms AI into a discussion partner instead of a shortcut. - Revision Logs.

Students document changes and explain their reasoning. The act of justification activates evaluative reasoning — the mental opposite of passive adoption. - Voice Check.

After revisions, students read their work aloud. If the tone no longer sounds like their own, they revise again. The goal is not perfection, but authenticity.

These approaches may slow the process slightly, but they restore what’s most valuable: thinking. Each step replaces cognitive debt with cognitive investment.

Equity and Access: The Hidden Dimension

Beneath the research numbers sits a quieter question: Who actually benefits from AI in writing—and who might quietly fall behind? The MIT researchers noticed that results depended heavily on each student’s self-awareness as a learner. Those who naturally planned, monitored, and questioned their work tended to guide the tool. Others, less confident in their process, often let it take the lead.

This pattern isn’t new. Every wave of educational technology has revealed the same truth: innovation doesn’t flatten differences—it stretches them. A well-prepared writer uses an AI essay grader as a lens to sharpen ideas; a struggling writer may mistake the lens for the work itself.

For multilingual learners, the issue becomes even more delicate. AI can model clear syntax and fluent phrasing, which can be a gift to students still mastering academic English. Yet when that support turns into dependence, a subtle cost emerges: the quiet fading of voice. True classroom writing should carry many rhythms and accents, not one polished tone.

The solution isn’t withdrawal but awareness. Students need to be taught how to question the machine—how to ask, “What part of my intent did this program miss?” That single act of reflection hands authorship back to them. The intelligence behind the text, after all, should remain human.

In the end, this crossroads between writing and AI isn’t really about software—it’s about attention. Writing has always been the mind thinking aloud. If AI is part of that process now, then our task is to make sure it amplifies the thinking, not replaces it.