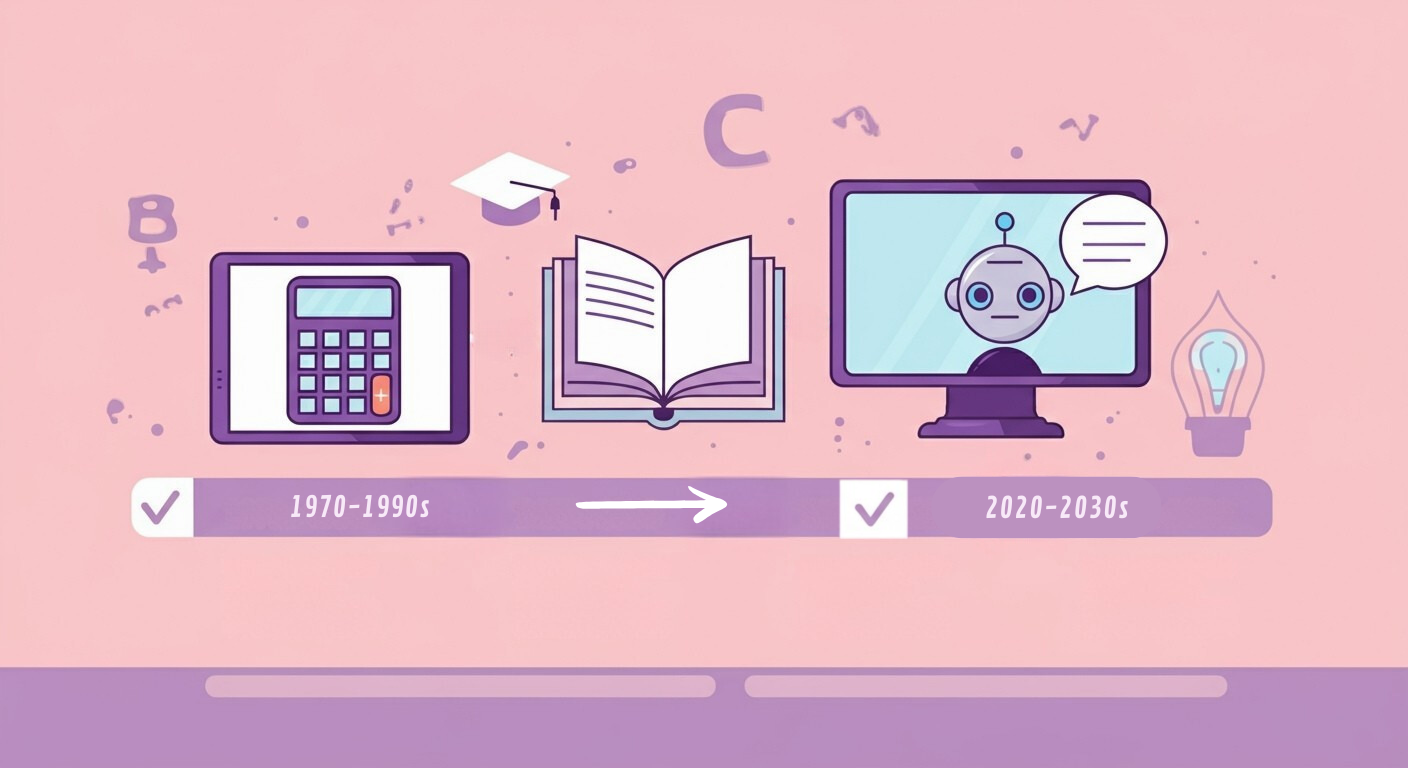

In the unfolding drama of education and technology, one cannot help but trace a parallel between the introduction of calculators into math classrooms and the gradual integration of Large Language Models (LLMs) into English instruction. The question is no longer if LLMs will become fixtures in the classroom, but when they will become as commonplace and indispensable as calculators. Just as calculators redefined the role of arithmetic in mathematical instruction, ai essay, LLMs are beginning to reshape the pedagogical landscape of language arts. Their current capabilities—offering feedback, aiding in brainstorming, revising drafts, and tutoring grammar—have already begun to challenge traditional notions of writing as an isolated, manual process.

Yet the evolution is not merely technological; it is epistemological. As Michel Foucault might argue, each educational tool is not just an instrument but a vessel for power, shaping what counts as knowledge, who holds it, and how it is deployed. With LLMs, we are witnessing a subtle shift in the architecture of authority: no longer does the teacher alone arbitrate the norms of grammar or the rhythm of a paragraph—AI is beginning to whisper its own suggestions into the student’s ear. Still, institutional caution persists. Schools flirt with adoption, while wary of AI’s potential for misuse, over-dependence, and embedded bias. These hesitations mirror the early debates over calculators: would they erode basic skills? Diminish intellectual rigor?

History offers a likely trajectory. In the short term—perhaps the next three years—LLMs will continue to play an auxiliary role, assisting with differentiated instruction and formative assessment. By the middle of the decade, curricular policy and teacher training may catch up, opening the door to official integration. Within a decade or so, LLMs could be as routine in English classrooms as calculators are in math, prompting a pedagogical shift toward teaching students how to evaluate, refine, and ethically use AI output. The emphasis, then, will not be on what students can write unaided, but how they can shape machine-generated drafts into coherent, creative, and authentic expressions of thought.

Of course, this integration will hinge on confronting several challenges. Just as calculators did not erase the need to understand multiplication tables, LLMs must not be allowed to displace foundational writing skills. Rather, they must be contextualized—seen not as threats but as tools for scaffolding student understanding. Access and equity will also be central; if LLMs are to democratize writing assistance, then they must be as available in underserved schools as they are in affluent ones. We must confront ethical issues—plagiarism, authorship, intellectual honesty—with clarity and nuance. Only when educators address these obstacles can the LLM truly claim its place alongside the calculator in the pantheon of educational technologies.

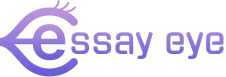

But how did the calculator come to occupy its current position of pedagogical normalization? Its journey was transformative. Before its arrival,ai essay math instruction focused on manual computation—drill and kill, memorization, procedural fluency. After calculators entered the classroom, emphasis shifted toward conceptual understanding and real-world problem solving. Students could now grapple with more complex problems earlier, freed from the labor of long division or logarithmic tables. Teachers, too, evolved—from deliverers of step-by-step processes to facilitators of mathematical reasoning and inquiry. Calculators not only reshaped curriculum and assessment but also raised new questions about dependence, equity, and cognitive development.

Critics, then and now, worried that calculators might undermine students’ numeracy, just as some now fear LLMs will erode writing fluency. But this fear underestimates the adaptability of pedagogy. Instruction adapted by balancing manual skills with technological proficiency, embedding calculator use into lessons without surrendering the fundamentals. The same must happen with LLMs. Students should still learn to construct a thesis, organize evidence, and refine their prose. The model must serve as assistant ai essay, not author.

This recalibration is already underway in how grammar is taught. The rigid sentence diagrams of yesteryear—the linguistic equivalent of abacuses—have largely faded. Today’s classrooms prefer functional grammar over formalism. Teachers focus on how grammar functions in communication rather than on diagramming it. While elementary grade students still learn the basics—nouns, verbs, clauses—they increasingly approach the deeper architecture of language through context-rich instruction, color-coded parts of speech, or digital tools that highlight syntax in real time. Diagramming is not extinct, but it survives mostly in classical education circles and specialized instruction, where it serves as a logic puzzle for the linguistically curious.

This shift away from sentence diagramming is not a dismissal of rigor but a recognition that pedagogy must evolve. Much like Foucault’s conception of discursive regimes, education reflects and reinforces broader societal norms. In an age defined by immediacy, interactivity, and algorithmic guidance, grammar instruction has adapted not by abandoning structure, but by reframing its purpose. And so we arrive at a crossroads, where the integration of LLMs is no longer a question of capability but of philosophical orientation. What do we want writing instruction to mean in an age when machines can mimic—and sometimes surpass—human prose?

If we look to the past, calculators did not diminish mathematics; they expanded its reach. They allowed students to engage with abstraction earlier and more deeply. With thoughtful implementation, LLMs could do the same for English—freeing students to focus on nuance, argument, tone, and voice. But the outcome depends on our choices. Will we treat LLMs as crutches, or as scaffolds? Will we craft new standards that embrace AI literacy as a core skill, or cling to models that no longer reflect the world students inhabit?

The future of English education, like that of math before it, is already being rewritten. AI grades may soon be a standard feature of classrooms, with students learning to evaluate their AI essays critically. The careful integration of these tools will redefine how we assess students’ capabilities—offering insights into not just what they produce, but how they navigate and refine the output provided by these models. AI grades will likely become as expected as calculator results in mathematics. Still, the focus should be on how students use AI essay assistance to craft original work while mastering the essential skills of thinking, writing, and communicating.